Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University

Paata Gugushvili Institute of Economics International Scientific

UNCOVERING THE DRIVERS OF LABOR MARKET INACTIVITY IN MIGRANT-SENDING HOUSEHOLDS IN GEORGIA

Annotation. This paper explored the existing interrelationships between migration and labor market outcomes of left-behind household members in Georgia. On the basis of the Georgian Household Survey, we explored alternative explanations of inactivity among left-behind members in migrant-sending households. In particular, the three effects are studied: the disincentive effects caused by additional non-labor income from remittances; substitution effect, which assumes performing a housework instead of participating at labor markets; and education effect which explains non-participation by engaging in higher education. Applying multinomial probit model, we ascertained that the accepted view on the labor market outcomes of migration according to which migration has a disincentive effect on labor participation of left-behind household members, providing them with extra incomes, is not true in Georgia. According to the findings of this study, in Georgia, migration affects inactivity on non-migrants mainly though substitution or education effects.

1. Background. The importance of the effects of migration and remittances on the labor market behavior (labor participation rate, supplied hours of work, employment types, educational attainment and etc.) of the left-behind household members is widely acknowledged in economic literature. The theoretical framework for the studies of this relationship is based on the assumption according to which the labor supply/leisure decisions of individual members of the household are less likely to be separable from each other (Chiappori, 1988; Chiappori et al., 2002; Fortin and Lacroix, 1997; Blundell et al., 2007; Berulava and Chikava, 2012; Belloc & Velilla, 2024). Growing number of empirical studies outlines the main channels through which migration and remittances can influence the labor market behavior of the left-behind members of migrant-sending households, including income and substitution effects, self-employment and educational decisions (Funkhouser, 1992; Rodriguez and Tiongson, 2001; Amuedo-Dorantes&Pozo, 2006; Acosta, 2006; Airola, 2008; Woodruff and Zenteno, 2001; Xu, 2017; Berulava, 2019; Habib, 2023; Uddin, 2023; Ndiaye et al., 2024).

A promising perspective for understanding the role of income and substitution effects in determining the impact of migration and remittances on labor supply of left-behind family members is presented in Görlich et al. (Görlich et al 2007) study. This article challenges the common statement that lower labor market participation level in migrant-sending families is only due to more leisure consumption. In particular, while considering the impact of out-migration on the household’s labor market outcomes, the authors distinguish the following three reasons of inactivity: 1) the disincentive or income effect, when left behind household’s members consume more leisure as a result of increased income from remittances; 2) labor substitution effect– replacing supplying labor to market by home work; and 3) education effect, which explains inactivity by engaging in higher education. Based on Moldova household survey data, the study finds weak evidence of disincentive effect. On the contrary, the authors argue that inactivity of individuals in migrant-sending households are explained mainly by intra-household labor substitution between the migrant working abroad and the inactive members left behind, as well as by greater probabilities of higher education enrollment.

It should be mentioned, that though relations between the migration and households’ labor market behavior has been studied intensively in Georgia (Danzer and Dietz, 2009; Gerber and Torosyan, 2013; OECD/CRRC-Georgia, 2017; Berulava, 2019), the perspective which explains the reasons of the inactivity of left-behind household members in this country, still remains relatively unexplored in economic literature and thus deserves a special interest. This study[1], based on the Georgian Household Survey, aims to fill existing gaps in this area of research by uncovering the drivers of labor market inactivity in migrant-sending households (specifically, we try to ascertain whether the inactivity is caused by income, substitution/housework or education effects).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Next section, illustrates the research methodology, including empirical strategy and measures. In section 3, we review the main characteristics of the sample and descriptive statistics. Further we discuss the results of the study. The final remarks are presented in the last section.

2. The Empirical Strategy. In this paper, we aim to understand the reasons of inactivity among left-behind members of migrant-sending households. To attain this objective, we apply the Multinomial Probit regression with instrumental variables. In particular, the estimation of the impact of migration on the reasons of inactivity of left-behind relatives, is conducted in two consecutive steps. First, we estimate probability of having a migrant in the household using the following probit regression model (1):

![]()

where yi is dummy variable, which equals to one when respondent lives in a household with at least one international migrant and zero otherwise; and yt* is associated with its latent variable. We define the yi as ‘migrant’ variable. The y1t;y2t; represent the vectors of parameters to be estimated, while εi is an error term which is assumed to follow a joint normal distribution with zero mean and variance equal to 1. The vector x1 include the independent variables, which influence an individual’s choice to participate at labor market, while and x2i is a vector of instrumental variables that affect only yi* but is excluded from the next structural equations, since the variables in this vector are not supposed to affect labor market behavior directly. The equation (1) in the essence is a reduced form equation, which performs auxiliary function, explaining variation in endogenous ‘migration’ variable using strictly exogenous variables x1i and x2i. The explanatory variables included in x1i and x2i vectors are described in more detail below.

The vector of control variables :

- Gender - is a dummy variable, which identifies respondent’s gender.

- Age – indicates respondent’s age.

- Age squared – square of respondent’s age.

- Marital status – is a dummy variable, which is equal to one if respondent is married and equals to zero otherwise.

- Head of Household – is a dummy variable, which is equal to one if respondent is head of household and equals to zero otherwise.

- Chronic illness – is a dummy variable, which is equal to one if respondent has at least one chronic illness and equals to zero otherwise.

- Education – reflects achieved level of education by respondent and is represented by a number of dummy variables: higher education, professional education; secondary education; below secondary education.

- Type of settlement – is a dummy variable, which is equal to one if respondent lives in urban areas and equals to two if respondent lives in rural areas.

- Log of non-labor income – is calculated as a natural logarithm of the household’s non-labor income.

- Max Education level – categorical variable, which reflects the maximum level of education achieved by household members

- Wealth – reflects general well-being of the households and is calculated as a factor score of assets and property which are at disposal of household

- Share of dependents – is calculated as ratio of children and pensioners to total household size.

The vector of instrumental variables x2i:

- Migration network (MN)– is calculated for each region of Georgian as a share of households with at least one international migrant in total number of households in this region.

- Migration network interacted with share of male adults (MNSA) – reflects interaction of migration network variable with the share of male adults in the household.

- Returned migrant – is a dummy variable, which is equal to one if there is at least one returned migrant in the household and equals to zero otherwise.

- Male Plus – is a dummy variable, which is equal to one if there is more than one adult mail in the household and equals to zero otherwise.

After the estimation of the equation (1), we predict the dependent variable and use predicted values of the ‘migrant’ variable as an independent factor at the next step. At the second stage, to deal with multiple choice problem we apply multinomial probit model as the estimation techniques. In general form, this model can be formulated as follows (Green, 2020):

![]()

where J -is number of alternatives, and -error term related to the alternative J. The probability of the choice of any particular alternative m can presented in the following form:

![]()

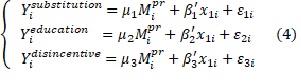

In this study, we distinguish between the three alternative reasons of inactivity:

- Inactivity_disincentive - inactivity due to disincentive effect, caused by extra money in household received from moved abroad migrant.

- Inactivity_sunbstitution - inactivity due to substitution effect, when left-behind member of household replaces participation at labor market by housework.

- Inactivity_education - inactivity due to education effect, when the youth left-behind member prefers to engage in higher education institution rather than to participate at labor market.

To proxy these three reasons of inactivity the disincentive, we employ a question from the Georgian household survey questionnaire, which asks inactive individuals for the reasons of their inactivity. Given three modes of inactivity, we apply the system of the following three equations:

where ![]() ; Yik is alternative reason of inactivity described above; Mpr is predicted value of ‘migrant’ variable obtained from the reduced-from equation; x1i- the vector of control variables similar to that in the system (1); μ1,μ2,μ3 are parameters and β1t;β2t;β3t - vectors of parameters to be estimated; ε1i;ε2i;ε3i;- error terms. We set the Inactivity_disincentive choice as a base category. The model is estimated simultaneously by simulated maximum likelihood estimation technique.

; Yik is alternative reason of inactivity described above; Mpr is predicted value of ‘migrant’ variable obtained from the reduced-from equation; x1i- the vector of control variables similar to that in the system (1); μ1,μ2,μ3 are parameters and β1t;β2t;β3t - vectors of parameters to be estimated; ε1i;ε2i;ε3i;- error terms. We set the Inactivity_disincentive choice as a base category. The model is estimated simultaneously by simulated maximum likelihood estimation technique.

3. Sample and Data Description. The main source of the data for the research is a nationally-representative, large-scale household survey conducted by Geostat[2] during the fourth quarter of 2012 among 2,784 households in all regions of Georgia except Abkhazia and South Ossetia regions. Since our study explores individual responses, we further will focus on the description of individual data. The total sample comprises 10,084 observations, of which 6,310 are of working age 15-65. Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics for the key variables used in the analysis.

Table 1. Summary statistics (means and std. deviations) for the analytical sample

|

Variables |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

|

Migrants |

0.0440 |

0.2052 |

|

Male (dummy) |

0.4755 |

0.4994 |

|

Age |

39.3 |

14.3 |

|

Married (dummy) |

0.6483 |

0.4775 |

|

Head of the Household (dummy) |

0.2554 |

0.4361 |

|

Chronic illness (dummy) |

0.1391 |

0.3461 |

|

High education (dummy) |

0.2489 |

0.4324 |

|

Professional education (dummy) |

0.2237 |

0.4168 |

|

Secondary education (dummy) |

0.4153 |

0.4928 |

|

Rural |

0.6207 |

0.4852 |

|

Non-labor income |

460.40 |

531.11 |

|

Share of dependents |

0.2918 |

0.2266 |

|

Inactive at labor market |

0.2581 |

0.4376 |

|

Inactive due to education effect |

0.0773 |

0.2671 |

|

Inactive due to housework |

0.1045 |

0.3060 |

|

Employed |

0.6358 |

0.4812 |

|

Hired employed |

0.2351 |

0.4241 |

|

Self-employed |

0.3980 |

0.4895 |

|

Unemployed |

0.1060 |

0.3078 |

As can be seen from the table 1, slightly more than 4% of households has at least one international migrant. The average non-labor income is around 460 GEL per month. The higher proportion of respondents live in rural areas (62%). More than 25% percent of the sample are inactive at labor market, including eight percent who are inactive due to engaging in higher education and more than ten percent who are involved in housework activities. Almost 64% percent of the sample are employed, including 23.5% of hired employed and almost 40% of self-employed. The demographic characteristics of the sample are as follows: 47,55% of the sample are males and on average a respondent is of 39.4 years old. Generally, more than 64 percent are married and 25.5% are household heads and about fourteen percent of the sample have at least one chronic illness. With regard to attained education level, almost 25% have higher education 22% professional, 41% secondary and the rest of the sample have only below secondary education.

4. Study Results. This section presents estimation results for the impact of migration on labor market behavior of the left-behind household members. In particular, we try to understand the reasons of inactivity-whether non-migrants are inactive due to income, substitution or education effect. Specifically, the three effects are studied: the disincentive effects caused by additional non-labor income from remittances; substitution effect, which assumes performing a housework instead of participating at labor markets; and education effect which explains non-participation by engaging in higher education. The estimation results of the multinomial probit model are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Multinomial probit model of the reasons of inactivity

|

Variables |

Education effect |

Substitution Effect |

||

|

Coefficient |

Bootstrapped S.E |

Coefficient |

Bootstrapped S.E |

|

|

Predicted value of ‘migrant’ |

0.6032** |

0.254 |

1.207*** |

0.228 |

|

Male (dummy) |

-0.682*** |

0.185 |

-4.276*** |

0.529 |

|

Age |

-0.415*** |

0.063 |

0.211*** |

0.041 |

|

Age squared |

0.333*** |

0.078 |

-0.336*** |

0.052 |

|

Married (dummy) |

-0.537** |

0.249 |

1.464*** |

0.176 |

|

Head of the Household (dummy) |

1.227** |

0.474 |

0.609** |

0.261 |

|

Chronic illness (dummy) |

-1.090*** |

0.405 |

-0.274 |

0.220 |

|

High education (dummy) |

-0.685 |

0.463 |

1.375*** |

0.328 |

|

Professional education (dummy) |

-2.568*** |

0.836 |

1.186*** |

0.292 |

|

Secondary education (dummy) |

-0.133 |

0.234 |

0.518** |

0.233 |

|

Type of settlement (1 -urban; 2 rural) |

-0.607*** |

0.202 |

0.102 |

0.156 |

|

Log of non-labor income |

-0.0218187 |

0.075 |

-0.206*** |

0.065 |

|

Maximum achieved educational level |

0.104*** |

0.047 |

-0.161*** |

0.049 |

|

Wealth (factor score) |

0.035*** |

0.007 |

0.024*** |

0.006 |

|

Share of dependents |

0.226 |

0.447 |

0.619* |

0.331 |

|

Constant |

7.513*** |

1.082 |

-2.197** |

0.873 |

|

Base category: Disincentive effect |

||||

|

Number of observations |

1,629 |

|||

|

Wald chi2(30) |

510.98 |

|||

|

Prob > chi2 |

0.0000 |

|||

|

Log pseudolikelihood |

-611.45622 |

|||

|

Notes: *** — significant at p < 0.01 level; ** — significant at p < 0.05 level; * — significant at p < 0.1 level. |

||||

In this model, the disincentive effect is used as a baseline category. Also, in this model, we consider only migrants who belong to a nuclear family. According to the table 2, having a migrant in a household significantly (at 1% level) increases probability of inactivity among non-migrant members due to education or substitution effects as compared to inactivity caused by disincentive matters. Other control variables used in the model, generally, have expected sign and statistical significance. The analysis of marginal effects of ‘migrant’ variable on inactivity reasons among left-behind household members presented in table 3, shows that living in migrant-sending household increases the probability of inactivity due to engaging in higher education by 1.2 percent. The substitution effect of migration is even stronger, the probability of replacing labor market participation by housework activities raises in migrant-sending households by 10.8 percent. The same time, the disincentive effect caused by extra income from migration is more than 12.0% less likely to occur in migrant-sending households.

Table 3. Marginal effects of migration on the reasons of inactivity of left-behind household’s members

|

Estimation technique |

Reasons of Inactivity |

||

|

Disincentive Effect |

Education Effect |

Substitution Effect |

|

|

Multinomial probit model |

-0.1203*** |

0.01204 |

0.1082*** |

|

Multinomial logit model |

-0.1233*** |

0.01455 |

0.1087*** |

|

Notes: in the table the average marginal effects are presented *** — significant at p < 0.01 level; ** — significant at p < 0.05 level; * — significant at p < 0.1 level. |

|||

To check the robustness of our model, we calculated the same effect using multinomial logit model. The marginal effects of migration in multinomial logit model presented in table 3, show little difference from those of multinomial probit model, thus suggesting that our results are robust.

To summarize, the accepted view on the labor market outcomes of migration is that migration has a disincentive effect on labor participation of left-behind household members, providing them with extra incomes. However, the results of our study don’t support this argument. According to the findings of this study, in Georgia, migration affects the inactivity of non-migrants mainly though substitution or education effects.

5. Conclusions. This paper explored the existing interrelationships between migration and labor market outcomes of left-behind household members in Georgia. On the basis of the Georgian Household Survey, we tried to answer the questions that remained relatively unexplored in economic literature. Specifically, we explored alternative explanations of inactivity among left-behind members in migrant-sending households. In particular, the three effects are studied: the disincentive effects caused by additional non-labor income from remittances; substitution effect, which assumes performing a housework instead of participating at labor markets; and education effect which explains non-participation by engaging in higher education. Applying multinomial probit model, we ascertained that the accepted view on the labor market outcomes of migration according to which migration has a disincentive effect on labor participation of left-behind household members, providing them with extra incomes, is not true in Georgia. According to the findings of this study, in Georgia, migration affects inactivity on non-migrants mainly though substitution or education effects.

This study is focused only on the extensive margins of the effect of migration on labor market outcomes. Further research should be focused on the exploration of the intensive margins of the effect of migration and remittances on labor variables of left-behind household members. Also applying time-series or panel data can provide better understanding of the casual link between migration and labor market behavior of the left-behind household members.

References

- ბერულავა გ., ი. დიხამინჯია; ნ. ღვინჯილია (2017). “მიგრაციის მიკროეკონომიკური ეფექტები შრომის ბაზარზე: საქართველოს მაგალითზე.” ეკონომისტი, 13 (4), გვ. 55-76

- Acosta, P., (2006). “Labor Supply, School Attendance, and Remittances from International Migration: The Case of El Salvador”. Policy Research Working Paper Series 3903, The World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org /curated/en/103531468234850236/pdf/wps3903.pdf

- Airola, J. (2008). “Labor supply in response to remittance income: The case of Mexico.” The Journal of Developing Areas, pp. 69-78.

- Amuedo-Dorantes, C., Pozo, A., (2006). “Migration, Remittances and Male and Female Employment Patterns”. American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings) 96 (2), pp. 222–226.

- Belloc, I., & Velilla, J. (2024). Collective Intrahousehold Labor Supply in Europe: Distribution Factors and Policy Implications. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, pp. 1-24.

- Berulava G. and G. Chikava (2012) “The Determinants of Household Labour Supply in Georgia, France and Romania: A Comparative Study”, Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, Vol. 5(9), 2012, pp. 141-164.

- Blundell R., P.-A. Chiappori, T. Magnac and C. Meghir (2007), Collective labor supply: Heterogeneity and nonparticipation, Review of Economic Studies 74, 417-455.

- Chiappori, P.-A. (1988) Rational household labor supply, Econometrica 56, 63-89.

- Chiappori, P.-A., Fortin, B. and G. Lacroix (2002) Marriage market, divorce legislation, and household labor supply, Journal of Political Economy vol.10(1), 37-72.

- Danzer Alexander M., and Barbara Dietz (2009) “Temporary Labour Migration and Welfare at the New European Fringe: A Comparison of Five Eastern European Countries.” IZA DP No. 4142.

- Fortin, B. and G. Lacroix, (1997) A test of neoclassical and collective models of household labor supply, Economic Journal 107, pp. 933-955.

- Funkhouser, E., (1992). “Migration from Nicaragua: Some Recent Evidence”. World Development 20, pp. 1209-1218.

- Gerber Theodore P., and Karine Torosyan (2013). “Remittances in the Republic of Georgia: Correlates, Economic Impact, and Social Capital Formation.” Demography, Springer, vol. 50(4), August, pp. 1279-1301.

- Görlich Dennis, Toman Omar Mahmoud, Christoph Trebesch (2007). “Explaining Labour Market Inactivity in Migrant -Sending Families: Housework, Hammock, or Higher Education”. Kiel Working Paper №1391, December, Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

- Green H. William., (2020). Econometric analysis. 8th ed. Prentice-Hall, Inc. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

- Habib, H. (2023). Remittances and labor supply: Evidence from Tunisia. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 14(2), pp. 1870-1899.

- Ndiaye, Ameth Saloum, and Abdelkrim Araar. (2024). "Migration and Remittances in Senegal: Effect on Households Members Left Behind." Journal of African Development 25, no. 1, pp. 95-129.

- OECD/CRRC-Georgia (2017), Interrelations between Public Policies, Migration and Developmentin Georgia, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264272217-en

- Rodriguez Edgar R. and Erwin R. Tiongson (2001), “Temporary Migration Overseas and Household Labor Supply: Evidence from Urban Philippines,” International Migration Review, vol. 35, № 3 Autumn, pp.709-725.

- Uddin, M. N. (2023). Impact of Migration on Time Use Pattern of Left-Behind Male and Female in Rural Bangladesh. Migration and Development, 12(2), pp. 215-235.

- Woodruff Christopher and Zenteno, Rene (2001), “Remittances and Microenterprises in Mexico”, UCSD, Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies Working Paper. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.282019.

- Xu, H. (2017). The time use pattern and labour supply of the left behind spouse and children in rural China. China economic review, 46, pp. S77-S101.

- Berulava G. (2019) “Migration and labor supply in Georgia: an empirical study.” Eurasian Economic Review, Springer, vol 9 (3), pp.395-419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40822-018-0106-4

[1] The detailed results of this study are presented in the following paper: ბერულავადასხვა (2017).

[2] National Statistics Office of Georgia, http://www.geostat.ge/index.php?action=0&lang=eng