Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University

Paata Gugushvili Institute of Economics International Scientific

CHALLENGES OF THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY: BARRIERS TO IMPLEMENTATION AND PATHWAYS TO PROGRESS

Annotation. The circular economy (CE) presents a transformative model for sustainable economic development by decoupling growth from resource consumption. While its theoretical and policy appeal is widely acknowledged, its practical implementation remains limited and fragmented. This paper explores the key challenges facing the circular economy, including institutional inertia, technological limitations, economic constraints, regulatory inconsistencies, and socio-cultural barriers. It argues that overcoming these challenges requires an integrated systems approach that aligns stakeholders across value chains, innovates governance structures, and redefines business and consumer behaviors.

Keywords: Circular economy, resource efficiency, sustainability transition

Introduction

The global economy is confronting mounting environmental, economic, and social pressures, including resource depletion, biodiversity loss, and escalating greenhouse gas emissions. In this context, the circular economy (CE) has emerged as a promising alternative to the dominant linear economic model of "take-make-dispose." Rather than relying on continual resource extraction and waste generation, the circular model emphasizes regenerative design, product-life extension, resource efficiency, and the closing of material loops through strategies such as reuse, repair, remanufacturing, and recycling. Over the past decade, the concept of the circular economy has gained substantial attention from policymakers, researchers, and industry leaders alike. It is increasingly integrated into international policy frameworks, including the European Green Deal and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). However, despite its growing theoretical and political appeal, the actual implementation of CE practices remains limited, fragmented, and uneven across geographies and sectors. This discrepancy between ambition and application underscores the need to critically examine the systemic barriers impeding circular transition. This article aims to contribute to this examination by identifying and analyzing the principal challenges that hinder the widespread adoption of circular economy principles. These challenges are grouped into five interconnected domains: institutional inertia, technological limitations, economic disincentives, socio-cultural resistance, and gaps in measurement and evaluation. Drawing on a qualitative synthesis of academic literature, policy analyses, and illustrative case studies, the paper not only categorizes these barriers but also outlines strategic pathways for overcoming them. In doing so, it provides a conceptual framework to support more effective policymaking, innovation, and stakeholder coordination in pursuit of a sustainable, circular future.

Research Methodology

This article employs a qualitative, exploratory research approach based on secondary data analysis. The study synthesizes findings from academic literature, policy reports, industry case studies, and institutional publications to identify and categorize the key challenges facing the circular economy. A thematic content analysis was conducted to group barriers into institutional, technological, economic, cultural, and measurement-related categories. Selected international case studies were used illustratively to contextualize challenges and highlight strategic responses. The methodology is interpretive and aims to provide a comprehensive conceptual framework rather than empirical measurement.

Conceptual Overview of the Circular Economy

The circular economy is grounded in principles such as waste minimization, product-life extension, resource efficiency, and closed-loop systems. It encompasses strategies including recycling, reuse, remanufacturing, sharing economies, and design for disassembly. The CE vision aligns with global agendas like the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goals 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and 13 (Climate Action). However, operationalizing these principles at scale involves significant restructuring of economic activities, value chains, and consumer habits. Institutional frameworks are often misaligned with CE objectives. [1] Many regulatory systems are optimized for linear economic models, with subsidies favoring resource extraction over reuse. Fragmented policy frameworks across local, national, and international levels hinder coordination and scalability. Moreover, government institutions frequently lack the capacity or mandate to facilitate circular practices, particularly in developing economies. The absence of clear metrics and standards for circularity further complicates implementation and monitoring. Transitioning to a circular economy demands advanced technological capabilities for materials tracking, reverse logistics, and eco-design. Many regions lack the infrastructure for large-scale recycling or remanufacturing. Technologies enabling product lifecycle management and circular supply chains such as blockchain, AI, and IoT are unevenly distributed and often costly to implement. In sectors like construction and textiles, legacy systems and material complexity further hinder technological integration. The economics of circular practices can be unfavorable compared to linear alternatives. High upfront investments, uncertain return on investment, and externalized environmental costs create disincentives for businesses. Additionally, price volatility in secondary raw material markets and lack of access to financing for circular startups stifle innovation. Traditional accounting models and business KPIs rarely capture circular value creation, making it difficult to justify transitions within existing corporate frameworks. [3]

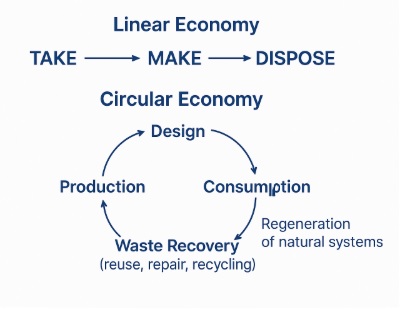

Diagram 1. Structural difference between the two models

(Linear Economy and Circular Economy)

Top Section: Linear Economy - TAKE → MAKE → DISPOSE, represents the traditional, unsustainable flow where resources are extracted, transformed into products, and discarded as waste—resulting in environmental degradation and resource depletion.

Bottom Section: Circular Economy - Design → Consumption → Waste Recovery → Production

- Emphasizes regenerative cycles where materials are reused, repaired, or recycled.

- Waste Recovery includes activities like reuse, repair, and recycling.

- Arrows loop back to Production, indicating continuous material circulation.

- Includes a note on "Regeneration of natural systems", aligning with CE’s broader ecological goals. [1]

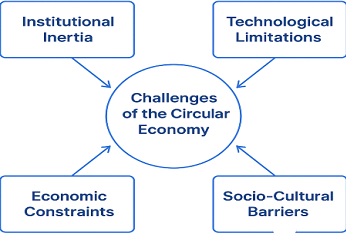

Diagram 2. Challenges of the Circular Economy

This diagram visually summarizes the four major categories of barriers discussed in your article:

ü Institutional Inertia – Legacy regulations, misaligned policies, lack of governmental capacity.

ü Technological Limitations – Insufficient infrastructure, costly innovation, uneven access to circular technologies.

ü Economic Constraints – High initial costs, low ROI, market failures, externalized environmental costs.

ü Socio-Cultural Barriers – Consumer resistance, lack of awareness, attachment to ownership and novelty. [3]

Knowledge Gaps and Measurement Issues

Consumer behavior remains a critical bottleneck. Circular consumption models such as product-as-a-service or repair and reuse require shifts in perception regarding ownership, convenience, and product value. Cultural attachment to newness, fast consumption cycles, and perceived hygiene risks (e.g., in clothing or personal care products) often obstruct market uptake. Moreover, businesses and consumers alike may lack awareness or understanding of circular options, necessitating substantial educational and behavioral change initiatives. Circularity is complex to measure. Traditional environmental and economic indicators inadequately capture the systemic nature of CE. Diverse definitions and taxonomies across institutions lead to inconsistencies in data reporting and impact assessment. [4] There is a need for unified metrics that can measure material circularity, social impact, and systemic resilience. Furthermore, academic and practical research remains siloed, limiting cross-sector knowledge exchange and innovation. Despite challenges, some industries and cities have demonstrated successful CE implementation. For example, Amsterdam has developed a city-wide circular strategy incorporating building materials, organic waste, and procurement policies. Companies like Philips and IKEA have integrated circular principles into product design and business models. However, these cases often benefit from unique regulatory support, access to innovation ecosystems, or consumer demographics favorable to circular models, raising questions about scalability and transferability. [2]

Strategic Pathways Forward

To address the above challenges, several strategic actions are proposed:

ü Policy alignment: Harmonizing regulations and incentives at multiple governance levels to support circular initiatives;

ü Public-private partnerships: Leveraging collaboration between industries, governments, and academia to drive innovation and resource sharing;

ü Investment in infrastructure and R&D: Supporting the development of circular technologies and logistics systems;

ü Education and engagement: Promoting awareness and capacity-building to foster behavioral change and cultural acceptance;

ü Metrics and standardization: Developing internationally recognized circularity indicators to guide investment, policy, and business strategy. [4]

Conclusion

The circular economy holds transformative potential, yet its adoption faces systemic challenges rooted in current institutional, technological, economic, and cultural paradigms. Addressing these barriers requires more than isolated innovation it demands a comprehensive redesign of socio-economic systems. With coordinated efforts and strategic foresight, the circular economy can evolve from an aspirational vision to a practical and inclusive model for sustainable development. The transition to a circular economy holds transformative potential for achieving sustainable development, yet it is obstructed by a complex web of institutional, technological, economic, and cultural barriers. Despite strong conceptual appeal and localized successes, the widespread implementation of circular principles remains hindered by systemic inertia and fragmented efforts. This article has highlighted that overcoming these barriers requires more than isolated initiatives; it demands a coordinated, systems-level approach involving regulatory reform, cross-sector collaboration, infrastructure investment, and societal engagement. Addressing measurement gaps and aligning incentives across governance levels will be essential to ensure accountability and guide strategic action. Ultimately, embedding circularity into the core of economic systems calls for a redefinition of value one that prioritizes resilience, regeneration, and long-term sustainability over short-term gains. As global pressures intensify, advancing the circular economy is not only a strategic opportunity but an ecological imperative.

References:

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2019). Towards the circular economy: Economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition. Ellen MacArthur Foundation;

- Geissdoerfer, M., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. P., & Hultink, E. J. (2019). The circular economy – A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production;

- Kirchherr, J., Reike, D., & Hekkert, M. (2020). Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling;

- Korhonen, J., Honkasalo, A., & Seppälä, J. (2021). Circular economy: The concept and its limitations. Ecological Economics;

- Lieder, M., & Rashid, A. (2022). Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. Journal of Cleaner Production;

- European Commission. (2023). A new Circular Economy Action Plan: For a cleaner and more competitive Europe;

- Schröder, P., Anantharaman, M., Anggraeni, K., & Foxon, T. (2019). The circular economy and the global south: Sustainable livelihoods, green jobs and industrialisation. Routledge.

- Ghisellini, P., Cialani, C., & Ulgiati, S. (2016). A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. Journal of Cleaner Production;

- Murray, A., Skene, K., & Haynes, K. (2017). The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. Journal of Business Ethics;

- Parchomenko, A., Borsky, S., & West, S. (2020). Measuring the performance of the circular economy: A review of indicators. Ecological Economics.